Abstracts

Sixteen opportunistic field observations of eight species of Brazilian raptors (Falconiformes and Strigiformes) are reported here as a contribution to the knowledge of the natural history of these poorly studied birds in Brazil. The observations are related to the food habits (Buteo albicaudatus, Herpetotheres cachinnans, Milvago chimachima, Falco femoralis), reproduction (Asio stygius, Megascops choliba), mobbing behaviour elicited in other birds (Geranospiza caerulescens, H. cachinnans, F. femoralis, A. stygius, Athene cunicularia) and a rare case of leucism in owls (A. cunicularia).

Falconiformes; Strigiformes; food habits; breeding; mobbing behaviour; leucism; Brazil

Dezesseis observações de campo oportunísticas, envolvendo oito espécies de aves de rapina brasileiras (Falconiformes e Strigiformes) são aqui relatadas como uma contribuição para o conhecimento da história natural dessas aves relativamente pouco estudadas em nosso país. As observações estão relacionadas aos hábitos alimentares (Buteo albicaudatus, Herpetotheres cachinnans, Milvago chimachima, Falco femoralis), reprodução (Asio stygius, Megascops choliba), comportamento de tumulto provocado em outras aves (Geranospiza caerulescens, H. cachinnans, F. femoralis, A. stygius, Athene cunicularia) e um caso raro de leucismo em corujas (A. cunicularia).

Falconiformes; Strigiformes; hábitos alimentares; reprodução; comportamento de tumulto; leucismo; Brasil

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS

Miscellaneous ecological notes on Brazilian birds of prey and owls

Notas ecológicas variadas sobre aves de rapina e corujas brasileiras

José Carlos Motta-JuniorI,* * Corresponding author: José Carlos Motta-Junior, e-mail: labecoaves@yahoo.com ; Marco Antonio Monteiro GranzinolliI; Alberto Resende MonteiroII

ILaboratório de Ecologia de Aves, Departamento de Ecologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo - USP, CEP 05508-090, São Paulo, SP, Brasil

IIInstituto de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento, Universidade do Vale do Paraíba - UNIVAP, CEP 12244-000, São José dos Campos, SP, Brasil, e-mail: montear@univap.br

ABSTRACT

Sixteen opportunistic field observations of eight species of Brazilian raptors (Falconiformes and Strigiformes) are reported here as a contribution to the knowledge of the natural history of these poorly studied birds in Brazil. The observations are related to the food habits (Buteo albicaudatus, Herpetotheres cachinnans, Milvago chimachima, Falco femoralis), reproduction (Asio stygius, Megascops choliba), mobbing behaviour elicited in other birds (Geranospiza caerulescens, H. cachinnans, F. femoralis, A. stygius, Athene cunicularia) and a rare case of leucism in owls (A. cunicularia).

Keywords: Falconiformes, Strigiformes, food habits, breeding, mobbing behaviour, leucism, Brazil.

RESUMO

Dezesseis observações de campo oportunísticas, envolvendo oito espécies de aves de rapina brasileiras (Falconiformes e Strigiformes) são aqui relatadas como uma contribuição para o conhecimento da história natural dessas aves relativamente pouco estudadas em nosso país. As observações estão relacionadas aos hábitos alimentares (Buteo albicaudatus, Herpetotheres cachinnans, Milvago chimachima, Falco femoralis), reprodução (Asio stygius, Megascops choliba), comportamento de tumulto provocado em outras aves (Geranospiza caerulescens, H. cachinnans, F. femoralis, A. stygius, Athene cunicularia) e um caso raro de leucismo em corujas (A. cunicularia).

Palavras-chave: Falconiformes, Strigiformes, hábitos alimentares, reprodução, comportamento de tumulto, leucismo, Brasil.

Introduction

Approximately 23% of all Falconiformes species and 11% of all Strigiformes species occur in Brazil (König et al. 1999, Ferguson-Lees & Christie 2001). In contrast, few raptor studies were conducted in this country, as commented by König et al. (1999) and Olmos et al. (2006). Here, we report original naturalistic observations on Brazilian birds of prey and owls, including food habits, breeding, mobbing behaviour and a case of leucism in owls. Food habits and reproduction are two important aspects of the biology of any animal. Though detailed food habit and foraging studies have been published for some Brazilian raptors (e.g., Motta-Junior & Bueno 2004, Sazima 2007, Granzinolli & Motta-Junior 2007) data on most species are scarce (see reports on Brazilian species in compilations such as König et al. 1999 and Ferguson-Lees & Christie 2001). Breeding studies on Brazilian raptors are even more difficult to find, with few specific published studies (e.g., Granzinolli et al. 2002, Lopes et al.2004, Carvalho-Filho et al. 2005, Specht et al. 2008), and scattered information in Sick (1997). Mobbing by birds against raptors is assumed to be an anti-predator adaptation (Curio et al. 1978), and virtually no specific study has addressed this topic in Brazil, except by some observations in Motta-Junior (2007) and Cunha et al. (2009). Finally, as incomplete albinism or leucism (sensu van Grouw 2006) in owls is extremely rare (Gross 1965, Alaja & Mikkola 1997), an example of leucism from south-east Brazil is also reported. Thus, the aim of this study was to present original data about the biology of some Brazilian raptors, contributing to increase the understanding of these birds.

Material and Methods

The observations were made opportunistically while the researchers conducted other field studies between 1988 and 2006 in Central and Southeast Brazil. The observations were grouped according to main themes, such as food habits, reproduction, leucism and mobbing behaviour elicited in other birds by raptors. Brief discussions after each observation are also included. Bird nomenclature is according to CBRO (2009).

Results and Discussion

1. Food habits

WHITE-TAILED HAWK BUTEO ALBICAUDATUS VIEILLOT, 1816 - ACCIPITRIDAE.

09/10/1998. Juiz de Fora municipality, Fazenda Ribeirão (21° 40' 00" S and 43° 24' 00" W). At 10:30 hours, ARM and MAMG found one individual of the snake Chironius sp. (Colubridae), in a nest of White-tailed Hawk. The body of the snake was damaged in several places and divided into three parts, the head missing. A 15-day-old nestling was in the nest feeding on the snake. The prey appeared to be fresh and had no strong odour, suggesting that it had been captured on the same day. The nest was located in an isolated tree in the middle of a pasture on hill, approximately 500 m from gallery forest.

11/11/1999. Juiz de Fora municipality, Fazenda Campo Grande (21° 40' 15" S and 43° 24' 02" W). At 12:27 hours, ARM and MAMG observed a White-tailed Hawk flying with a snake in its talons over a pasture area. The hawk rose on a thermal air current and dropped the snake in the air, immediately diving and catching it again 20 m from the ground; it then rose again and repeated the action. Next it carried the snake to its nest, which was being monitored and contained two nestlings. The nest was checked and a snake (Bothrops jararaca Wied-Neuwied, 1824) was found completely lacerated, with the greatest damage to its anterior part. The diet of the White-tailed Hawk is one of the most well studied in relation to others raptors in Brazil (see Granzinolli & Motta-Junior 2007). However, the data about snakes in the diet are mentioned in family level, and according to Granzinolli & Motta-Junior (2007), the analysis of 259 pellets (3296 prey items) in south-east Brazil yielded eight individuals, all of them Colubridae. The first record of a Viperidae snake in the diet of White-tailed Hawk here reported reveals this raptor can prey on poisonous snakes.

LAUGHING FALCON HERPETOTHERES CACHINNANS (LINNAEUS, 1758) - FALCONIDAE.

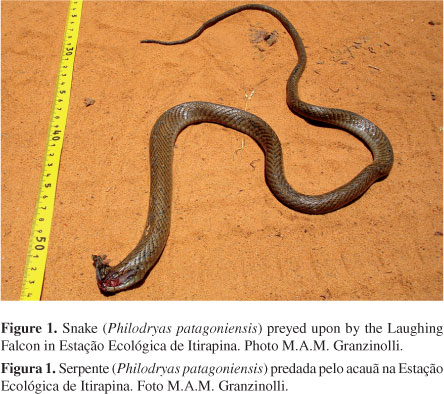

18/01/2006. Estação Ecológica de Itirapina (22° 14' 43" S and 47° 53' 09" W). At 08:13 hours, MAMG observed a Laughing Falcon hunting a snake in a "campo sujo" (grassland with scattered shrubs). The falcon has been previously perched on a pole, and then it was observed dropping to the grassland ground. When the observer approached, the bird flew back up to the pole about 20 m away. The raptor let the snake fall to the ground, without its head, a Philodryas patagoniensis Girard, 1858 (Colubridae) weighing 84 g (Figure 1). The Laughing Falcon prey almost exclusively on snakes, including large and venomous ones (White et al. 1994, Ferguson-Lees & Christie 2001, Specht et al. 2008). However, detailed reports on positively-identified snakes are rare (Sazima & Abe 1991, Sazima 1992, Duval et al. 2006). This report confirms the Laughing Falcon's herpetophagous habits and includes a new and relatively large snake as its prey.

YELLOW-HEADED CARACARA MILVAGO CHIMACHIMA (VIEILLOT, 1816) - FALCONIDAE AND WHITE-TAILED HAWK BUTEO ALBICAUDATUS - ACCIPITRIDAE.

25/01/2000. Prata municipality, Parque Florestal Salto e Ponte III (19° 10' 12" S and 48° 48' 19" W). At 17:28 hours, approximately 12 Yellow-headed Caracara and one White-tailed Hawk were observed by JCMJ hunting winged termites (Termitidae) and catching them directly in their bills during flights above a gallery forest. No agonistic behaviour was observed between the raptors. This event and the swarming of the winged termites occurred soon after a short rainfall. In spite of the size of these raptors (315-335 g for Yellow-headed Caracara and 850-884 g for White-tailed Hawk, (see Thiollay 1994, White et al. 1994) several bouts were observed on those tiny preys. This behaviour was previously observed for other Falconiformes, as in the genera Caracara and Milvago (Sazima 2007), the Plumbeous Kite Ictinia plumbea (Gmelin, 1788) (Robinson 1994, Sick 1997) and the Aplomado Falcon Falco femoralis Temminck, 1822 (see below).

APLOMADO FALCON FALCO FEMORALIS - FALCONIDAE.

02/09/2006. Itirapina municipality (22° 15' 36" S and 47° 47' 49" W). Between 18:07 hours and 18:17 hours MAMG observed an individual of the Aplomado Falcon taking flying winged termites Cornitermes cumulans Kollar, 1832 (Termitidae) with its foot and bringing them to its bill. The falcon was flying in circles about 3-5 m high in an ecotone pasture-woodland savannah. At least 100 termites were captured and consumed during 10 minutes of observation. A similar predation rate (over 100 termites during 15 minutes) was observed by Robinson (1994) for the Plumbeous Kite. Though energetically each insect was almost insignificant, the easy capture and large number of these prey probably compensate for the energy spent by the raptors. Sick (1997) reported previously the consumption of flying alate termites by the Aplomado Falcon.

08/02/2006. Estação Ecológica de Itirapina (22° 11' 44" S and 47° 54' 49" W). At 18:31 hours, during a tracking telemetry, MAMG found one male Aplomado Falcon eating a White-rumped Monjita Xolmis velatus (Lichtenstein, 1823). The falcon was perched on a tree in a "campo cerrado" holding the dead prey in its talons. This observation corroborates its ornithophagous diet (Ferguson-Lees & Christie 2001) and adds a positively-identified bird species as prey of this falcon.

2. Reproduction

STYGIAN OWL ASIO STYGIUS (WAGLER, 1832) - STRIGIDAE.

30/09/1991. Granja do Ipê, Brasília (15° 56´ S and 47° 52´ W). A nest was found by JCMJ in a "campo de murundus" or a floodplain grassland with scattered earth-mounds including shrubs and small trees. This physiognomy is associated with the Cerrado biome in central Brazil (Oliveira & Marquis 2002). The nest was located on one of these earth-mounds in a shallow depression on the ground just below the cover of a small Roupala montana Aubl. (Proteaceae) shrub less than 1.0 m in height. Two recently hatched nestlings with white feathers and closed eyes were found. An adult had flown away with the approach of the observer and was later mobbed by a White-tailed Hawk (see below in the section about mobbing behaviour). This nest is very similar to that described by Lopes et al. (2004), also in central Brazil, and scattered information on literature suggests that the ground is the main site for nesting (Bond 1942, Scherer-Neto 1985, Franz 1991, Holt et al. 1999, König et al. 1999). However, Oliveira (1981), Holt et al. (1999) and König et al. (1999) have also reported the use of abandoned stick nests of other birds in trees.

TROPICAL SCREECH OWL MEGASCOPS CHOLIBA (VIEILLOT, 1817) - STRIGIDAE.

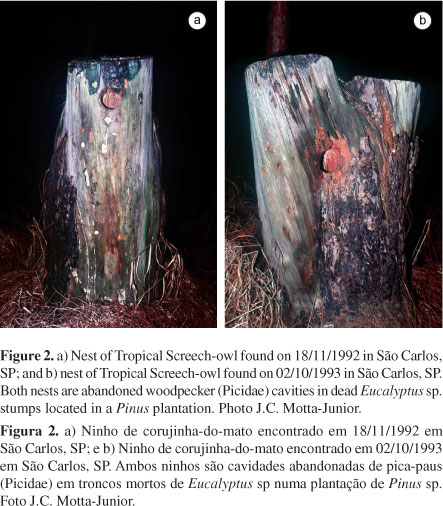

18/11/1992. Nest found by JCMJ in a dead Eucalyptus sp. stump in the understory of a Pinus plantation, Chácara Mattos, São Carlos municipality (22° 00´ 18" S and 47° 55´ 44" W). The surroundings of the Pinus plantation consisted of secondary grassland savannah and sugar-cane plantation. The cavity entrance was at 75 cm above ground and was 9 cm in diameter and 31 cm deep (Figure 2a), presumably made by a woodpecker (Picidae). An adult female and two owlets that were a few days old (whitish feathers and closed eyes) were found in the cavity.

02/10/1993. Another nest of this species was found in the same locality and habitat, also in a dead Eucalyptus stump (Figure 2b). The abandoned woodpecker cavity was at 60 cm above the ground, 8 cm in diameter and 28 cm deep, where an adult female was brooding three white eggs. At 13/10/1993, an adult and only two recently hatched owlets were found. Although there are rare data on nest sites for the Tropical Screech-owl, the observations in this study support the few published accounts (Smith 1983, Holt et al. 1999, König et al. 1999) and suggests that this species uses mainly tree trunk cavities like the general pattern for the genus Megascops (=Otus) (König et al. 1999).

3. Mobbing behaviour against raptors

CRANE HAWK GERANOSPIZA CAERULESCENS (VIEILLOT, 1817) - ACCIPITRIDAE.

09/06/1988. Fazenda Água Limpa, Brasília (15° 56´ 39" S and 47° 54´ 29" W). At approximately 17:00 hours, JCMJ observed a group of at least 40 individuals of the Red-bellied Macaw Orthopsittaca manilata (Boddaert, 1783) - Psittacidae perched on Mauritia flexuosa L. (Palmae) trees along a gallery forest. Some individuals were resting and others were feeding on Mauritia fruits. Suddenly, a transient Crane Hawk elicited loud vocalizing from the macaw group and raised them into flight, pursuing the raptor for at least 1 minute, but no physical contact was observed. Ferguson-Lees & Christie (2001) reported this hawk taking young parrots from tree holes, the habitual nest location for the Red-bellied Macaw (Gonzalez 2003).

LAUGHING FALCON HERPETOTHERES CACHINNANS - FALCONIDAE.

25/01/2000. Prata municipality, Parque Florestal Salto e Ponte III (19° 10' S and 48° 48' W). At approximately 17:00 hours, in a palm swamp forest ("vereda", see Oliveira & Marquis 2002), JCMJ detected a Laughing Falcon perched on a M. flexuosa tree, vocalizing its typical call. Suddenly the falcon was chased by ten individuals of White-eyed Parakeet Aratinga leucophthalma (Statius Muller, 1776), soon followed by a pair of the larger Red-bellied Macaw (both species Psittacidae). The hawk flew away but was pursued by all these psittacids for about one more minute. Though the Laughing Falcon is supposed to be herpetophagous (Sick 1997), this observation suggested that this raptor may occasionally prey upon birds (see Ferguson-Lees & Christie 2001).

APLOMADO FALCON FALCO FEMORALIS - FALCONIDAE.

16/02/2006. Brotas municipality, Fazenda Sonho Meu II (22° 19' 01" S and 48° 01' 26" W). At 8:09 hours, MAMG saw an Aplomado Falcon perched on a pole inside an orange plantation. After a few minutes, two Guira Cuckoos Guira guira (Gmelin, 1788) made three swooping flights at the raptor's head. In the last attack, the falcon left the pole, since one of the cuckoos struck its head. The fleeing falcon was chased by the cuckoos for at least two more minutes.

17/02/2006. Estação Ecológica de Itirapina (22° 11' 40" S and 47° 55' 03" W). At 15:36 hours, MAMG observed two Yellow-bellied Elaenias Elaenia flavogaster (Thunberg, 1822) striking an Aplomado Falcon perched on a tree in "campo cerrado" (grassland savannah). After some close raids without physical contact, the falcon flew 10 - 15 m above the tree in circles. The Yellow-bellied Elaenia pursued the raptor for about 3 minutes. Then, the falcon perched in another tree 30 m away from the first, and no more agonistic behaviours by the elaenias were observed. As this falcon is largely ornithophagous (Ferguson-Lees & Christie 2001) it is supposed to naturally cause more mobbing activity (Gehlbach & Leverett 1995).

STYGIAN OWL ASIO STYGIUS - STRIGIDAE.

30/09/1991. Granja do Ipê, Brasília (15° 56´ S and 47° 52´ W). JCMJ observed, at 15:52 hours, a White-tailed Hawk attacking, in four swooping flights, a Stygian Owl perched on a tree in a "campo de murundus". Indeed the hawk never made physical contact with the owl, but only swooped at it. The owl simply adopted a defensive posture, fluffing its feathers and stretching the wings to appear bigger. After the last swoop, the hawk moved away. Although hawks are known to occasionally prey on owls (Mikkola 1983), this behaviour was considered a mobbing event, because no fight or attempt to capture the owl was observed.

BURROWING OWL ATHENE CUNICULARIA (MOLINA, 1782) - STRIGIDAE.

14/12/1993. Luiz Antônio, Estação Experimental de Jataí (21° 34´ 33" S and 47° 44´ 04" W). There are rare evidence of mobbing against this owl (see Altmann 1956), but on the morning JCMJ observed two Chalk-browed Mockingbirds Mimus saturninus (Lichtenstein, 1823) - Mimidae mobbing an owl perched on the ground in a pasture. In the afternoon, in the same pasture, another individual owl was mobbed by a Tropical Kingbird Tyrannus melancholicus Vieillot, 1819 (Tyrannidae). Since then we never observed any event of mobbing on the Burrowing Owl in Brazil, suggesting its rarity (Altmann 1956), which can be partially explained by the fact that the Burrowing Owl seldom preys on birds (Motta-Junior & Bueno 2004).

4. Leucism in owls

BURROWING OWL ATHENE CUNICULARIA - STRIGIDAE

November - December 1996. Chácara Mattos, São Carlos municipality (22° 00´ S and 47° 55´ W). During this month JCMJ observed a leucistic Burrowing Owl living along with other normally pigmented individual (Figure 3) in disturbed grassland surrounded by Pinus plantations and suburbs of the city. The individual had feathers completely white and the bill was yellowish. Eyes and legs were also normally pigmented. According to van Grouw (2006) this is a case o leucism. The leucistic's behaviour was apparently normal for the species in the few occasions it was observed. After December 1996 the leucistic disappeared from the area. Leucism is apparently rare in this species, as apart from our observation, only one report has been published for the Burrowing Owl in the United States, although considered as incomplete albinism (Ajala & Mikkola 1997). However, following van Grouw (2006) it is actually a leucism case, as it is not possible the occurrence of partial or incomplete albinism.

Acknowledgments

Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) provided financial support for some of JCMJ and MAMG field trips. ARM was supported by Fundo Nacional do Meio Ambiente (FNMA). Maria Alice dos Santos Alves, Ivan Sazima, and an anonymous referee were helpful with their comments. Adriana A. Bueno revised the English text. Ricardo Chaves helped with the identification of termites. A.W. Faber-Castell S/A allowed visits at Chácara Mattos and supported field trips to Parque Florestal Salto e Ponte III.

Received 14/06/2010

Revised 29/09/2010

Accepted 10/11/2010

- ALAJA, P. & MIKKOLA, H. 1997. Albinism in the Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa) and other owls. In Biology and conservation of owls of the Northern Hemisphere (J.R. Duncan, D.H. Johnson & T.H. Nicholls, eds.). General Technical Report NC-190. USDA Forest Service, North Central Research Station. St. Paul, Minnesota, p.33-37.

- ALTMANN, S.A. 1956. Avian mobbing behavior and predator recognition. Condor 58:241-253.

- BOND, J. 1942. Notes on the devil owl. Auk 59:308-309.

- CARVALHO-FILHO, E.P.M., CARVALHO, G.D.M. & CARVALHO, C.E.A. 2005. Observations of nesting Gray-headed Kites (Leptodon cayanensis) in southeastern Brazil. J. Raptor Res. 39:89-92.

- CBRO - Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos. 2009. Listas das aves do Brasil. Versão 9/08/2009. http://www.cbro.org.br/CBRO/listapri.htm (last access in 28/04/2010).

- CUNHA, F.C.R., VASCONCELOS, M.F. & SPECHT, G.V. A. 2009. Alerta vermelho! Caburé na area! Ciência Hoje 43(257):26-29.

- CURIO, E., ERNST, U. & VIETH, W. 1978. Cultural transmission of enemy recognition: one function of mobbing. Science 202:899-901.

- DUVAL, E.H., GREENE, H. W. & MANNO, K. 2006. Laughing Falcon (Herpetotheres cachinnans) predation on coral snakes (Micrurus nigrocinctus). Biotropica 38(4):566-568.

- FERGUSON-LEES, J. & CHRISTIE, D.A. 2001. Raptors of the world. Houghton and Mifflin Company, New York.

- FRANZ, M. 1991. Field observations on the Stygian Owl Asio stygius in Belize, Central America. J. Raptor Res. 25:163.

- GEHLBACH, F.R. & LEVERETT, J.S. 1995. Mobbig of Eastern Screech-owls: predatory cues, risk to mobbers and degree of threat. Condor 97:831-834.

- GONZÁLEZ, J.A. 2003. Harvesting, local trade, and conservation of parrots in the northeastern Peruvian Amazon. Biol. Conserv. 114:437-446.

- GRANZINOLLI, M.A.M. & MOTTA-JUNIOR, J.C. 2007. Feeding ecology of the White-tailed Hawk (Buteo albicaudatus) in south-eastern Brazil. Emu 107:214-222.

- GRANZINOLLI, M.A.M., RIOS C.H.V., MEIRELES, L.D. & MONTEIRO, A.R. 2002. Reprodução do falcão de coleira Falco femoralis Temminck 1822 (Falconiformes: Falconidae) no município de Juiz de Fora, sudeste do Brasil. Biota Neotrop. 2(2): http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v2n2/en/fullpaper?bn01902022002+pt (last access in 28/04/2010).

- GROSS, A.O. 1965. The incidence of albinism in North American birds. Bird Banding 2:67-71.

- HOLT, D.W., BERKLEY, R. DEPPE, C., ENRÍQUEZ-ROCHA, P.L. OLSEN, P.D., PETERSEN, J.L., RANGEL-SALAZAR, J.L., SEGARS, K.P. & WOOD, K.L. 1999. Strigidae species accounts. In Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. 5: Barn owls to hummingbirds (J. del Hoyo, J. Elliot. & J. Sargatal, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, p.152-242.

- KÖNIG, C., WEICK, F. & BECKING, J.H. 1999. Owls: a guide to the owls of the world. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

- LOPES, L.E., GOES, R., SOUZA, S. & FERREIRA, R.M. 2004. Observations on a nest of the Stygian Owl (Asio stygius) in the central Brazilian cerrado. Ornitol. Neotrop. 15:423-427.

- MIKKOLA, H. 1983. Owls of Europe. Buteo Books, Vermillion.

- MOTTA-JUNIOR, J.C. & BUENO, A.A. 2004. Trophic ecology of the Burrowing Owl in southeast Brazil. In Raptors Worldwide (R. Chancellor & B.U. Meyburg, eds.). Working world group of birds of prey and owls/MME-BirdLife Hungary, Berlin and Budapest, p.763-775.

- MOTTA-JUNIOR, J.C. 2007. Ferruginous Pygmy-owl (Glaucidium brasilianum) predation on a mobbing Fork-tailed Flycatcher (Tyrannus savana) in southeast Brazil. Biota Neotrop. 7(2):321-324. http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v7n2/en/fullpaper?bn04407022007+en (last access in 15/04/2010).

- OLIVEIRA, P.S. & MARQUIS, R.J. 2002. The Cerrados of Brazil: ecology and natural history of a Neotropical savanna. Columbia University Press, New York.

- OLIVEIRA, R.G. 1981. A ocorrência do mocho-diabo (Asio stygius) no Rio Grande do Sul. An. Soc. Sul-Riogrand. Ornitol. 2:9-12.

- OLMOS, F., PACHECO, J.F. & SILVEIRA, L. F. 2006. Notas sobre aves de rapina (Cathartidae, Accpitridae e Falconidae) brasileiras. Rev. Bras. Ornitol. 14:401-404.

- ROBINSON, S.K. 1994. Habitat selection and foraging ecology of raptors in Amazonian Peru. Biotropica 26:443-458.

- SCHERER-NETO, P. 1985. Notas bionômicas sobre o mocho-diabo (Asio stygius Wagler, 1832) no Paraná. An. Soc. Sul-Riograndense Ornitol. 6:15-18.

- SICK, H. 1997. Ornitologia brasileira. 2 ed. Nova Fronteira, Rio de Janeiro.

- SMITH, S.M. 1983. Otus choliba. In Costa Rican natural history (D.H. Janzen, ed.). University of Chicago Press, Chicago, p.592-593.

- THIOLLAY, J.M. 1994. Accipitridae species accounts. In Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. 2: New World vultures to guineafowl (J. del Hoyo, J. Elliot. & J. Sargatal, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, p.52-205.

- WHITE, C.M., OLSEN, V.D. & KIFF, L.F. 1994. Falconidae species accounts. In Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. 2: New World vultures to guineafowl (J. del Hoyo, J. Elliot. & J. Sargatal, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, p.216-275.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

29 July 2011 -

Date of issue

Dec 2010

History

-

Accepted

10 Nov 2010 -

Reviewed

29 Sept 2010 -

Received

14 June 2010